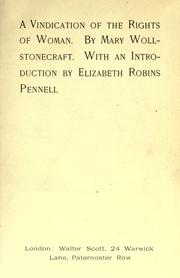

He said he had “put down the leading traits of her intellectual character.” But, on a principle of candor, he had put down much more. In a wash of grief-work, he immersed himself in writing Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published January 1798. The midwife, weirdly, was her adoring husband, William Godwin. But four months after her death in September 1797, another “Wollstonecraft” was born: a menace and a monster, an atheist, a slut, a pathology, and a castrating threat to male authority. Aside from some reactionary snipes at its language of a “revolution” in her call for reforms, Wollstonecraft’s good sense was generally appreciated. How surprising, then, that such a vindicator could go dim for nearly a century under a cloud of disgrace. Uniforms, too: not only to get rid of vanity but also to efface class differences. The visionary horizon of Rights of Woman is an educational utopia: free, national day-school coeducation, on a curriculum of intellectual subjects and physical activity for both sexes. Girls are “made women, almost from their very birth” by what they are told and how they are managed, how they are trained to be weak, irrational, and dependent and then admired for these qualities while they are being oppressed by the same. Women’s so-called inferiority, she contended, is due to miseducation. Wollstonecraft invokes a Creator who has endowed all human creatures with rational capacity. The famous motto of the French Revolution, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, had turned out to be a fraternity after all, denying women citizenship and substantive education. What of the genre, Vindication? More than “Thoughts on” or even that eighteenth-century favorite, “Letters on,” it’s a polemical defense, an assertive justification.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)